(Below is Michael Wearing’s obituary written by Simon Farquhar, for The Times. Thanks to Simon for allowing the obituary to be shared here.)

When Michael Wearing gave screenwriter Andrew Davies a copy of Michael Dobbs’ novel House of Cards in 1989, suggesting he dramatise it for the BBC, he said, intuitively: “it’s not very good but it’s got a great plot. It wants a bit of tweaking. Think Jacobean”.

With ideas now flourishing in his mind of a charismatic villain who talks directly to the audience, Davies was on his way to creating three series of immaculate drama that proved so popular that they even inspired a surprisingly successful American incarnation. Wearing’s was a masterful piece of guidance that exemplified what made him one of the most incisive and supportive drama producers in the BBC’s history, a man who skilfully fought to tell stories he felt were worth telling, a man undervalued by the broadcaster who he had provided with some of its greatest successes during some of its most troubled times.

The single play, which Wearing had learnt his craft working on, traditionally the space that allowed original voices the freedom to say original and often radical things, had been a threatened institution for twenty years, due to its habit of upsetting the apple cart. Finally, in a new, nervous and more accountable BBC, it was a form that would gradually be abandoned in favour of genre serials. But, despite his frustrations, Wearing’s superb record of creating sophisticated popular successes showed that stimulating television could still be made if producers had his blend of courage and good taste.

As well as the knavish House of Cards, which he saw as “a racy story about power, money and sex, and one I thought the BBC should tell”, two other wildly different works stand as a testament to those qualities: Troy Kennedy Martin’s nuclear conspiracy thriller Edge of Darkness (1985) and Alan Bleasdale’s savage, funny and despairing Boys From The Blackstuff (1982). Each of the serials were political to a greater or lesser degree, each boldly reimagined traditional storytelling techniques on television, and each was a phenomenally successful exploration of something that was wrong with Eighties Britain.

Wearing was a man of pleasing contradictions, affable without being easy, earthy yet elegant, as distinctive for his graceful hand gestures as for his gravelly laugh, an admirer of the bon mot whose eyes would light up if he inadvertently coined one. He enjoyed good wine and good company, but unlike many in the convivial atmosphere of the BBC bar in the 1970s, he was also disciplined and quietly determined, more interested in those who created drama than those who caused it, not a man who went out of his way to please people or to mollify those who supposedly needed mollifying. Those traits won him passionate admirers and dangerous enemies.

Even his much-imitated working-class accent, incongruous in the hushed upper echelons of the BBC, made him instantly recognisable as a different kind of animal. He was a grammar-school boy, the son of Douglas, a Stock Exchange clerk, and Molly (nee Dawson), born in Southgate, North London. His performance at Dame Alice Owen’s school in Islington earned him a place reading anthropology at Durham University. He then worked as a research assistant at the University of Leeds, during which time his fast and funny production of Max Frisch’s The Chinese Wall took the Sunday Times Cup at the 1967 National Student Drama Festival and landed three nights at the Garrick. The production starred his future BBC colleague, Alan Yentob, but the judge, critic Harold Hobson, was decidedly grumpy when announcing their victory. Wearing, with a candour and irreverence he would later become celebrated for, told the press: “Hobson could have been more constructive in his criticism. It’s a bit much when five universities spend hundreds of pounds and he finds more to say on a fellow journalist than on the plays”.

The triumph was enough of an encouragement for him to quit his research job for the theatre, first working as an assistant stage manager at Bromley Rep, impressing with Muck For Three Angels at the Traverse, then being invited to direct at the Royal Court. The attitude of a theatre dedicated to new writing was one which Wearing thrived on, and he carried its mentality with him throughout the rest of his career, even if directing wasn’t his best expression of it. He helmed the eagerly-awaited but disastrous follow up to Hair, Isabel’s a Jezebel (1970), and later directed a couple of television plays, but the producer’s chair would prove his natural home.

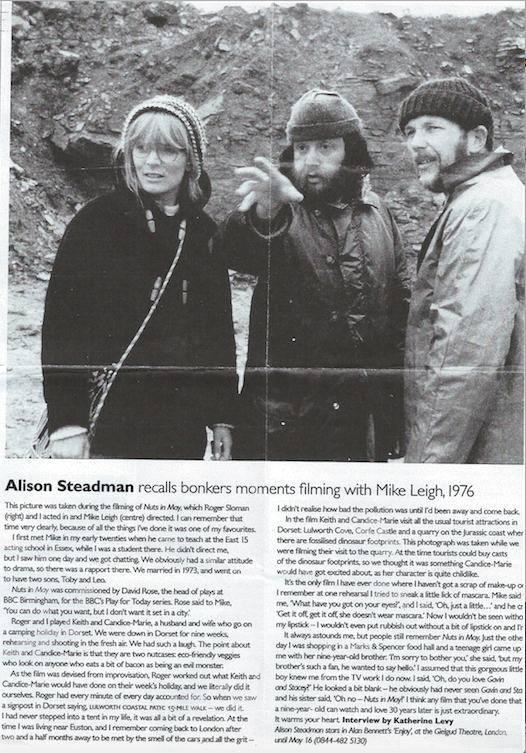

His route to it came via one of television’s great impresarios, David Rose, in his new role as the BBC’s Head of English Regions Drama. Rose was impressed by Wearing’s touring (via transit van) production of Gogol’s Diary of a Madman, and brought the production to television. The piece stunned the critics, and led Rose to invite Wearing to join the team as a script editor.

Initially a quiet and tentative member of this creative powerhouse, he worked diligently, gradually growing in confidence, and upon becoming a producer, inherited a gift of a serial in Malcolm Bradbury’s concupiscent The History Man (1981), a campus saga of gross moral turpitude that had already outraged as a novel and which vividly established Wearing’s credentials as a producer unafraid of whipping up a storm. Boys From The Blackstuff, with its confrontational depiction of a Britain crumbling both spiritually and economically under the weight of unemployment, was again a project which guaranteed controversy and governmental displeasure.

Wearing then took over as producer for the final season of Play for Today in 1984. The strand had been dying of neglect since the turn of the 1980s, lacking the innovation and courage that had made it such a force for good throughout the previous decade, but under his command there were some final triumphs, such as Barrie Keefe’s King, exploring the exploitation of the Windrush generation as they neared retirement age, and Doug Lucie’s horrifying study of a spiteful, privileged metropolitan elite, Hard Feelings.

Wearing was never afraid to make life difficult for himself if it might yield good work: Edge of Darkness meant having to rely on a writer as unpredictable and undisciplined as Troy Kennedy Martin, whose original pitch was “detective who turns into a tree”. The finished work perfectly expressed Britain’s growing fear that the Cold War might be hotting up for a nuclear winter. Another BAFTA winner was First And Last (1989), Michael Frayn’s story of a retired everyman (Joss Ackland) walking from Land’s End to John O’Groates. A road movie on foot and a long-distance love story, the huge production was hit not only by inconsistent weather but by tragedy when its original star, Ray McAnally, died half-way through shooting, but the finished film remains a gentle masterpiece.

As Head of Serials, as well as inevitably controversial works of the highest quality such as Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia (1993), he became a late convert to period drama, overseeing the BBC’s massive renaissance and reinvigoration of the genre after the success of Pride and Prejudice (1995).

An executive role thankfully never smoothed his rough edges: at a weekly programme review meeting, after listening to two senior BBC figures dissing a recent and challenging serial, Grushko (1994), Wearing, rather than disassociating himself from the production, told them “you’re both completely wrong. I think it’s a really important piece that is very well made and one that isn’t easy with its audience”.

He was awarded BAFTA’s Alan Clarke Award in 1997 and the RTS Cyril Bennett Award the following year, but with the arrival at the BBC of John Birt, an invasion by consultants, an obsession with ratings and the centralisation of the decision-making process, Wearing was driven disgustedly to resign and set up his own production company. Within a few hours of the announcement, 300 people signed a petition of support for him. A former colleague later bumped into him in Soho and “he said to me: ‘one day I’ll talk to you about betrayal’”.

Wearing was modest in his achievements, a gregarious but unpretentious character who lived at arm’s length from the showbiz world, in Peckham, where he shared a home for over twenty years with the artist Karen Loader. They had two children, Ella, an artist, and Benjamin, a cinematographer. He was previously married for twenty years to Jean Ramsay, with whom he had two daughters, Sadie, an academic, and Catherine, herself an exceptional television producer, who predeceased him.

Although there has been a flowering of impressive drama again at the BBC in the last two years, Wearing remained justifiably angry that “there is now nowhere for new, original voices to be heard. New writers are trained on how to write EastEnders instead”. There remains an unjustifiable gap in the schedules for the kind of work he believed in. As producer Kenith Trodd said at the time of Wearing’s resignation: “the symbolism of the BBC becoming a place where Michael Wearing cannot exist is very, very ominous”.

Michael Howard Wearing, producer, born 12 March 1939, died 5 May 2017

Simon Farquhar