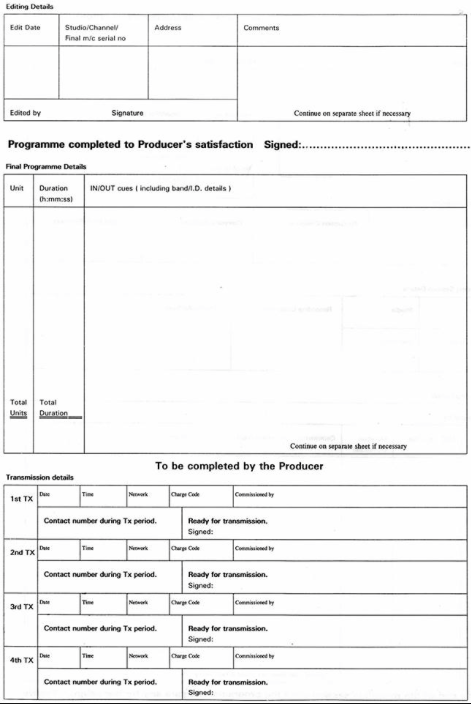

Twenty years ago, I started working at BBC Pebble Mill. It was an extraordinary place. By no means perfect, it had something we don’t have any more: a huge mix of talent.

From Robin Vanag’s Flickr

Landing at the BBC’s then Birmingham base after twenty-plus years in commercial radio. I couldn’t believe my eyes: unheard-of skills, facilities, staffing and space.

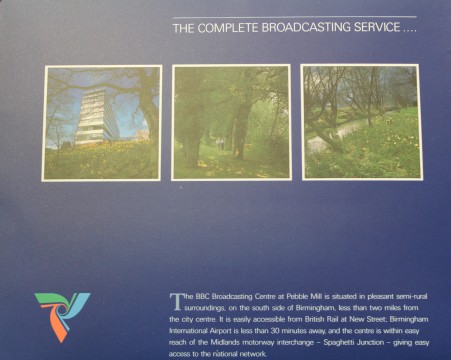

Space? Oh yes, there was space. Pebble Mill had lush, extensive, landscaped gardens, perfect to lounge in on summer lunchtimes, and a canteen, a clubhouse and a bar. There were tennis courts beyond the clubhouse. The place boasted an on-site medical facility in case you went sick. You could enjoy subsidised aromatherapy and yoga sessions. There were dressing rooms for the TV people, and showers if you wanted to go for a run in nearby Cannon Hill Park. And hundreds of people of all shapes, sizes and skillsets worked there.

It could not have presented a bigger contrast to the world of commercial radio.

The splendour! The empires! The drawbacks!

Pebble Mill also had all the awful trappings of a large organisation. There were empires to protect and maintain, barriers to prevent progress, favouritism and worse. I also met a disconcerting amount of elitist snobbery reserved for commercial radio incomers.

I was there to set up the playout systems for, and then to produce, the overnight shows for BBC Radio 2. That meant I had six hours a day to look after. This was rather more than any other producer in the building, some of whom had to wrestle with, ooh, as much as 45 minutes a week. It wasn’t a stretch: at BRMB/XTRA, across town, I’d looked after 42 hours of programming each day.

But the music made it an engrossing and wonderful task. Radio 2 had range and depth. It still does, and that’s one of the reasons it continues to grow and prosper. We catered for the station’s overnight audiences with some splendid, if touchy, presenters.

I had joined a team that provided impressive specialist programming. Radio 3 took a large chunk of Pebble Mill output. From the same department, Folk, Country, Blues, Big Band shows and more flowed out to Radio 2. And a steady stream of Sony Awards flowed back to Pebble Mill’s broadcasters.

The Archers’ staircase from BBC website

Walking deeper into the block, you penetrated – cautiously – into Archers territory. One week in four, the Archers’ cast filled a generously appointed green room area, waiting to speak their lines in the fabled Studio 3. Studio 3 bristled with special effects. It had a genuine Aga stove with real pots to bang, every kind of door and window closure you could imagine, with flagstones and slabs to walk across. At the back, a flight of stairs had three different surfaces. This allowed people to be recorded climbing or descending carpeted, concrete or steel steps. There was a ‘stable’ with leftover reel to reel tape on the floor to sound like straw, or fire when the script called for it. The place had hundreds of sound effects, marked up and sorted so you could hear Dan Archer starting his car, or a tractor coming in to the yard.

Slipping past the Archers cast’s frosty glances, you passed a more conventional studio, Studio 5. There never was a Studio 4; it became an office instead. Finally you came to the two studios that hosted Radio 2’s overnight shows, with an office for the tiny team that looked after them.

The studios were at the end of the block, as far as you could go. So the aged air conditioning struggled to cool the place down on hot summer nights. There was a quantity of new-fangled computer kit in Studios 6 and 6a, which generated a lot of heat.

That was the network radio side. The television side, where I rarely ventured, was just as lavish and productive. The list of shows that came out of those studios from the 70s to the 90s is long and varied. Then, beyond these two blocks, there were five floors of administration. The canteen was on the top floor, offering sunny views over leafy Edgbaston. Corner offices catered to the most senior of managers.

All told, this was a splendid set of facilities, with magnificent people to match. By the standards of the day, it was luxurious and expansive. That said and acknowledged, pretty much the first thing I heard after I arrived was how bad things had become. I didn’t believe it, and I didn’t care. I’d come out of commercial radio, where every penny spent on programmes had to be fought for.

from Media UK. 15 years of BBC 2 growth

I didn’t care because I had such a great gig. This was at the start of Radio 2‘s move from uncool and obscure to radio giant.

Think, if you will, of the 90s station as an ancient beloved aunt who smelled of dust and lavender.

As the station swung into the 21st century, that aunt had morphed into a sleek, hot forty-something. She smelled a lot more expensive, and she showed a daring amount of skin. And she reached a lot more people.

The Beeb gets wise

In truth, by the early 90s, the BBC was only just beginning to cotton on to the fact that commercial radio had been doing a lot of things right. Old stagers there could not begin to imagine that there might be better, faster, and more efficient ways to deliver great programmes. Others did, like my far-sighted bosses, Geoffrey Hewitt and Owen Bentley, who gave me my head for five fruitful years.

I think it could and should have gone on for longer, but sadly, Pebble Mill fell victim to a venomous internal market. John Birt’s infamous ‘producer choice’ policy set departments against each other. Radio 2 teams in London resented their colleagues in Birmingham for winning the funding for Overnights. Departments that should been collaborating for the greater good of the BBC – a public service organisation – competed instead.

In the end, the London teams got it all back; they usually do. They went on to grab a host of other shows along the way, shows that Pebble Mill had quietly and efficiently produced for decades. That spelled the end for network programming from Birmingham to any significant degree. Pebble Mill, a hive of creativity and cost-efficient production. was sidelined. As best as I could tell, there was no serious examination of its flaws and assets, costs or long term development.

Decline and fall

At the end of the 90s, and on through the noughties, month by month, one by one, BBC Birmingham’s brilliant staffers exited the organisation. They either quit, disillusioned and demoralised, or they were sacked, or they moved to work for the BBC elsewhere. The decision was taken to move from Pebble Mill, which was on a peppercorn rent, to a more expensively rented city centre location: the Mailbox. This was a smaller place, with no television facilities save those used for regional news. Whole radio networks moved to Manchester. Key television shows moved, north and south. In fairness, new technology was also bringing in massive change, freeing producers from fixed locations. But no attempt was made to keep production centres in the region, and so the talent leaked away.

The radio block and beyond

Once in the Pebble Mill building, you went past reception and down to a crossroads of passageways. There you turned left to the radio block. Its spine was a long, wide, institutional corridor with lots of 70s wood panelling. On the left was the huge Studio 1, built for live audiences. On the right Pebble Mill boasted a magnificent multi-track music studio, Studio 2. It could hold maybe 60 musicians. Two weeks after I arrived, I found the CBSO rehearsing on the left, while Van Morrison, Georgie Fame and the BBC Big Band were rocking hard on the right. But that was not a typical day.

Pebble Mill flattened

Pebble Mill was emptied of staff and mothballed. Then it was stripped of all its equipment. Eventually the wreckers moved in to tear everything down. Pebble Mill road became a place where, finally, you could park your car. For a decade, the site lay empty, a sea of rubble. I’d drive past and look; it was a strange feeling. Now, a new medical campus is being built to tie in with other facilities a mile down the road.

I wasn’t the only one who looked. If you search online, there’s a wealth of nostalgic shots of the flattened site, taken by ex-staffers. Here’s one from Elliott Brown’s flickr page.

A critical creative mass

It’s not the buildings that I miss, though, fond though I became of the place. There was a critical mass of creative people in broadcasting in Birmingham twenty years ago. Now? There just isn’t. I met and worked with people of undisputed genius. It was inspiring. There was experience and knowledge so different, so far beyond what I had been used to up to that point. I dealt with craft skills I’d never encountered before. Ideas were exchanged and lives enriched.

But please don’t think that it was anything approaching perfect. Pebble Mill, like every place, had its share of bullies and vain, stupid, lazy people. Like everywhere else, you learned to work around them when you could. But the exchange of ideas, the richness of many strands of knowledge, and the extraordinary, diverse, creativity was something rare and precious. It was invaluable, and it won’t – it can’t – be replaced.

Maybe something new and 21st century will emerge, aided by digital technology. I really would love to see that happen; nothing would give me greater pleasure. But ideas need champions and talent needs gatekeepers, mentors and coaches. Pebble Mill had all that. We need those people back now, for the sake of the coming generations of broadcast talent.

Robin Valk