Copyright resides with the original holder, no reproduction without permission.

This article is from the Birmingham Post from 1961. It is a portrait of the architect of BBC Pebble Mill, John Madin, and the role he was having in rebuilding 1960s Birmingham.

Here is a transcript of the article:

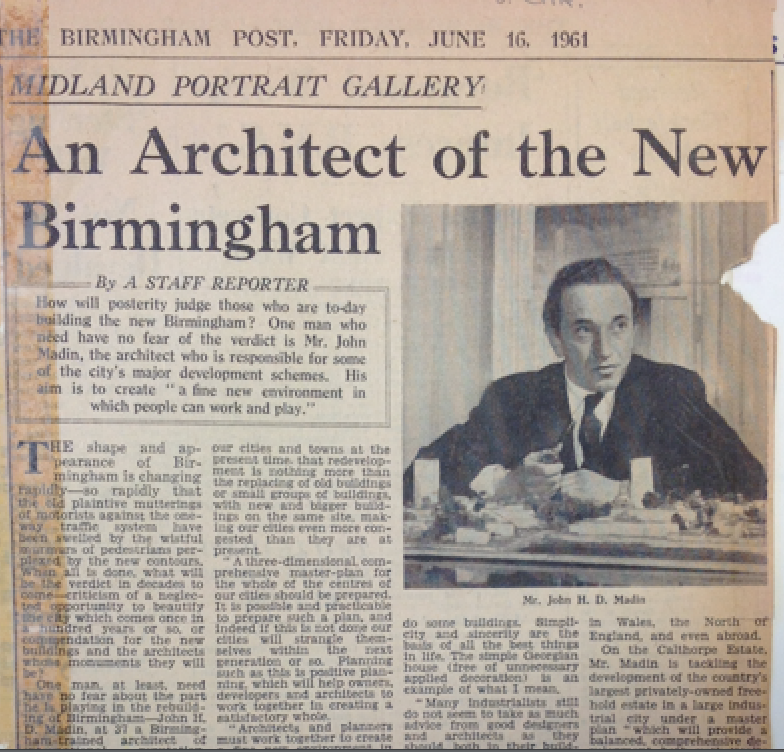

Midland Portrait Gallery

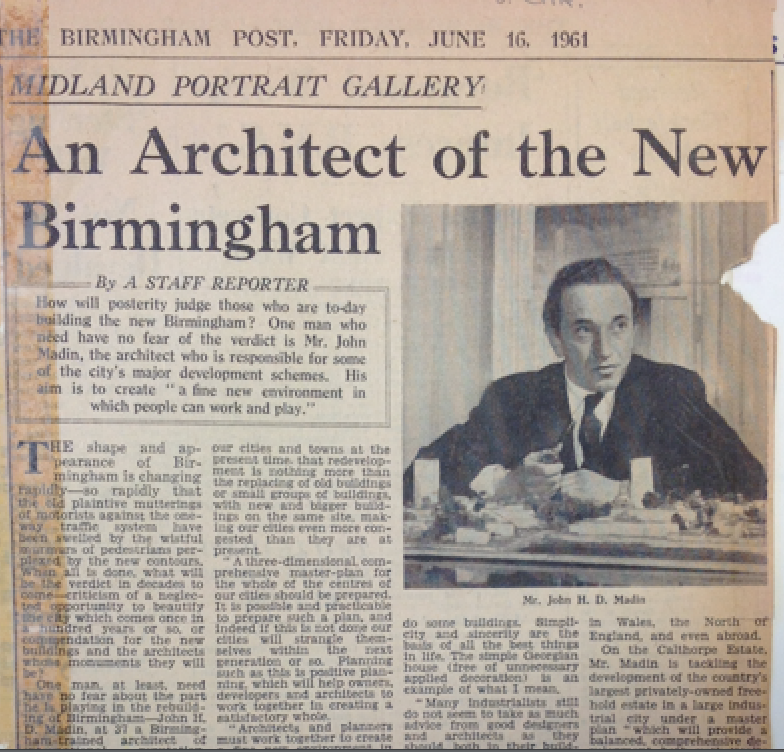

An Architect of the New Birmingham

By a Staff Reporter

How will posterity judge those who are today building the new Birmingham? One man who need have no fear of the verdict is Mr John Madin, the architect who is responsible for some of the city’s major development schemes. His aim is to create “a fine new environment in which people can work and play.”

The shape and appearance of Birmingham is changing rapidly – so rapidly that the old plaintive mutterings of motorists against the one-way traffic system have been swelled by the wistful murmurs of pedestrians perplexed by the new contours. When all is done, what will be the verdict in decades to come – criticism of a neglected opportunity to beautify the day which comes once in a hundred years or so, or commendation for the new buildings and the architects whose monuments they will be?

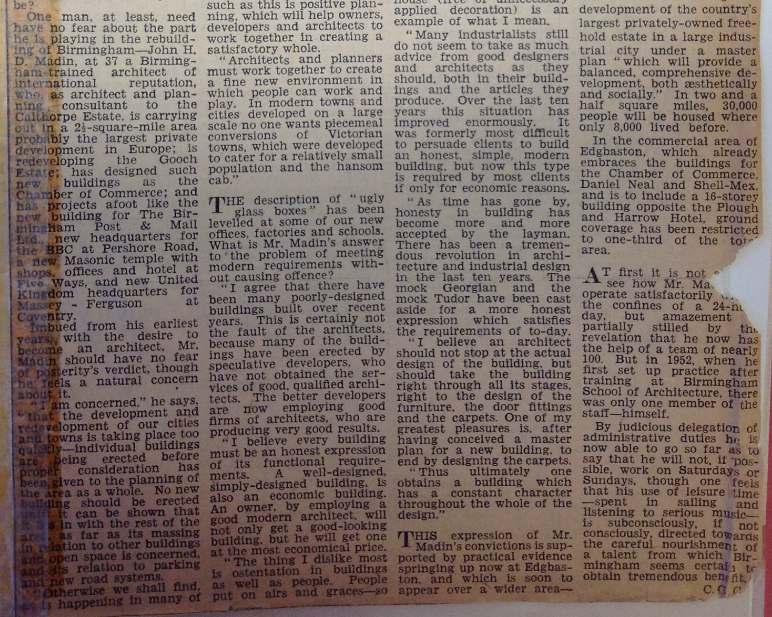

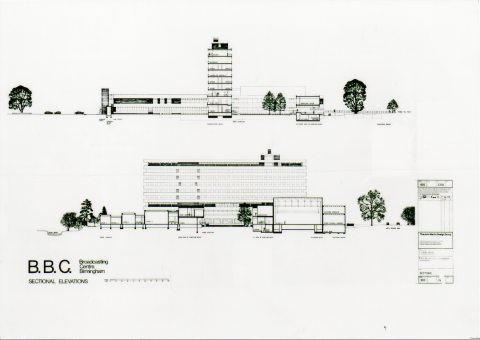

One man, at least, need have no fear about the part he is playing in the rebuilding of Birmingham – John H D Madin, at 37 a Birmingham trained architect of international reputation, who, as architect and planning consultant to the Calthorpe Estate is carrying out in a 2 ½ square mile area probably the largest private development in Europe; is redeveloping the Gooch Estate; has designed such new buildings as the Chamber of Commerce; and has projects afoot like the new building for The Birmingham Post and Mall Ltd, new headquarters for the BBC at PErshore Road, a new Masonic temple with shops, offices and hotel at Five Ways, and new United Kingdom headquarters for Massey Ferguson at Coventry.

Imbued from his earliest years with the desire to become an architect, Mr Madin should have no fear of posterity’s verdict, though he feels a natural concern about it.

“I am concerned,” he says, that the development and redevelopment of our cities and towns is taking place too quickly – individual buildings are being erected before proper consideration has been given to the planning of the area as a whole. No new building should be erected until it can be shown that it is in with the rest of the areas, as far as its massing in relation to other buildings and open space is concerned, and its relation to parking and new road systems.

“Otherwise we shall find, as is happening in many of our cities and towns at the present time, that redevelopment is nothing more than the replacing of old buildings or small groups of buildings with new and bigger buildings on the same site, making our cities even more congested than they are at present.

“ A three-dimensional, comprehensive master-plan for the whole of the centres of our cities should be prepared. It is possible and practicable to prepare such a plan, and indeed if this is not done our cities will strange themselves within the next generation or so. Planning such as this is positive planning, which will help owners, developers and architects to work together in creating a satisfactory whole.

“Architects and planners must work together to create a fine new environment in which people can work and play. In modern towns and cities developed on a large scale no one wants piecemeal conversions of Victorian towns, which were developed to cater for a relatively small population and the hansom cab.”

The description of “ugly glass boxes” has been levelled at some of our new offices, factories and schools. What is Mr Madin’s answer to the problem of meeting modern requirements without causing offence?

“I agree that there have been many poorly designed buildings built over recent years. This is certainly not the fault of the architects, because many of the buildings have been erected by speculative developers, who have not obtained the services of good, qualified architects. The better developers are now employing good firms of architects, who are producing very good results.

“I believe every building must be an honest expression of its functional requirements. A will designed, simply designed building, is also an economic building. An owner, by employing a good modern architect, will not only get a good looking building, but he will get one at the most economical price.

“The thing I dislike most is ostentation in buildings as well as people. People put on airs and graces, so do some buildings. Simplicity and sincerity are the basis of all the best things in life. The simple Georgian house (free of unnecessary applied decoration) is an example of what I mean.

“Many industrialists still do not seem to take as much advice from good designers and architects as they should, both in their buildings and the articles they produce. Over the last ten years this situation has improved enormously. It was formerly most difficult to persuade clients to build an honest, simple, modern building, but now this type is required by most clients if only for economic reasons.

“As time has gone by, honesty in building has become more and more accepted by the layman. There has been a tremendous revolution in architecture and industrial design in the last ten years. The mock Georgian and the mock Tudor have been cast aside for a more honest expression which satisfies the requirements of today.

“I believe an architect should not stop at the architect should not stop at the actual design of the building, but should take the building right through all its stages, right to the design of the furniture, the door fittings and the carpets. One of my greatest pleasures is, after having conceived a master plan for a new buildings, to end by designing the carpets.

“Thus ultimately one obtains a building which has a constant character throughout the whole of the design.”

This expression of Mr Madin’s convictions is supported by practical evidence springing up now at Edgbaston, and which is soon to appear over a wider area – in Wales, the North of England, and even abroad.

On the Calthorpe Estate, Mr Madin is tackling the development of the country’s largest privately owned freehold estate in a large industrial city under a mast plan “which will provide a balanced, comprehensive development, both aesthetically and socially.” In two and a half square miles, 30,000 people will be housed where only 8,000 lived before.

In the commercial area of Edgbaston, which already embraces the buildings for the Chamber of Commerce, Daniel Neal and Shell-Mex, and is to include a 16 storey building oppositie the Plough and Harrow Hotel, ground coverage has been restricted to one-third of the total area.

At first it is not easy to see how Mr Madin can operate satisfactorily within the confines of a 24 hour day, but amazement partially stilled by the revelation that he now has the help of a team of nearly 100. But in 1952, when he first set up practice after training at Birmingham School of Architecture, there was only one member of the staff – himself.

By judicious delegation of administrative duties he is now avle to go so far as to say that he will not, if possible, work on Saturdays or Sundays, though one feels that his use of leisure time – spent in sailing and listening to serious music – is subconsciously, if not consciously directed towards the careful nourishment of a talent from which Birmingham seems certain to obtain tremendous benefit.

CGC