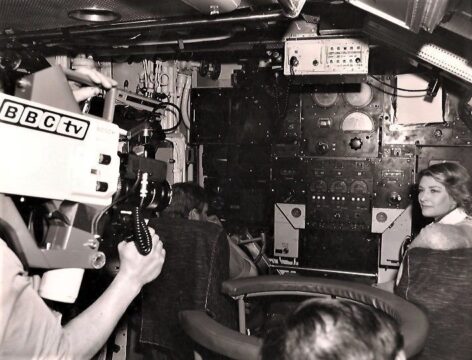

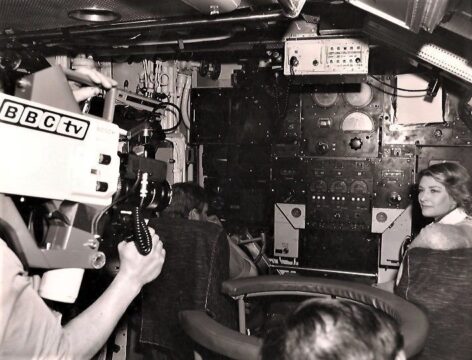

Pebble Mill at One, Bosch Fernseh camera, on location on HMS Dreadnought, 1980

We had the use of a Bosch Fernseh ( KCN92 I think) in the early 80’s, I don’t know if it belonged to us or it was borrowed on long term loan etc. It was used both in studios and on outside broadcasts, from what I can remember it was not very reliable but to be fair other lightweight cameras of its generation were no better. I remember us having a Link lightweight camera from Bristol for one Pebble Mill at One, presumably the Fernseh was unwell, It came with engineers and a lot of equipment that was rigged in front of the Studio A line-up desk. By the time of the dress run it was in disgrace and was been de-rigged.

The break though came when we obtained an Ikegami HL79A. This appeared to be a reliable stable camera, which did not require a hip-pack or other box between the camera head and control unit (CCU). Due to its reliability it was trusted to do stand alone single camera work. At the time the only VT recorder available to us was a 2” Quad Portable. Yes, there was such a beast. It had a suitcase carrying handle on the case and took up two thirds of the back seat of a Ford Cortinia, just leaving room for the operator. Vacuums were not involved like its big brothers, but it was still noisy, hence often been banished to the back of a car away from the microphones. When back at the Mill, the twenty minute tapes were spliced together to make the editing easier.

The next break through was when we borrowed from London 1” B format Bosch BCN20. I think that we might have had two. This was a much smaller recorder, but still with a segmented scan which meant that playback could only be done at normal speed, unlike the new C format machines, so accurate logging of the material was still paramount.

With the increased successful use of our single camera unit, production demands were increasing. We were expected to arrive at a location more often, likely outside with no power available, quickly set up do a recording and on to the next location and on and on, often until the light faded. To put it in context, this was in the days when with large OB units the crew travelled in the morning, after lunch the cameras were rigged, made to work, the producer had a look-see at shots then the crew was stood down, until the next day. This new way of working was not popular with all. I remember hearing a camera supervisor saying, “the lightweight revolution, four times the work for the same money”. With multiple moves to locations sometimes only around the corner it was clear that we could not keep cabling the various bits up, and it was not always an option to keep the kit rigged in the car and just run the camera cable out. The camera cable was not able to be of a very long length as the cable terminated in a passive control box that just enabled iris, sit and colours to be adjusted. I bought an aluminium sack truck so the VT could go on the bottom. They still weighed about 1/2 cwt (25Kg in today’s money) and the monitor could go on the top. I think I got the idea after using a sack truck loaned by a spark who took pity on us manhandling the kit. A few years later there was a lot of purpose built trolleys on the market, but back in the early 80’s there was very little specialist equipment about, especially suitable battery powered devices.

There was the ongoing problem was viewing the monitor in bright sunlight. A blanket or large plastic bag could be thrown over the widows of a car, but I can remember having to resort to lying under a blanket to view the monitor in the Lake District, but I was soon joined by the producer who decided viewing the shots was more important than preserving his dignity. I was told that we would have had a lot of explaining to do if a member of the public had come across a blanket with two pairs of legs emerging from underneath. I remember amusement at ‘Glorious Goodwood’. I think we were doing something with Omar Sharif, when well oiled punters saw me sitting down underneath a plastic bag or blanket and one of the crew members said I was all right, it was just too much champagne. Once the monitor was mounted on a sack truck life was more dignified.

I have many happy memories of these times, and as times passed all the jobs tend to merge into one. We were lucky to have producers at Pebble Mill who were keen to talk to the operational staff and come back with ideas to how they could best utilise the facilitates that we could offer and provide new challenges. This sense of working together was contagious and often spread to the talent (sorry for that Americanism) who would often carry equipment and run cables. One of the shows that stands out was going around the East End of London, before the soap Eastenders with producer Roger Casstles, when we were told on camera in Smithfield Market with the Old Bailey in the background by one of the stars that that was where he made his acting debut in front of a audience of twelve. Roger asked him if wished us to retake, I can’t remember the outcome.

As well as working for Pebble Mill producers, our services were requested by others, we were sent at short notice to a drama were it had overrun and the London Lightweight Scanner (LPU) had had to go to another booking, when I pulled up in the car, probably a Cortinia estate, there was a group of people including actors who looked at me and asked where the Scanner was. I probably felt like saying, this is as good as it gets, but thought that I had to be more diplomatic. As well as doing single camera work with our trusty “Ike” we had built up bits to use the Philips LDK 14 cameras on our two camera Lightweight Unit CM2 in a battery mode. These cameras although designed as an ENG camera connected via a multiway cable up to 100’ I think, to a LDK 514 converter box to enable it to be connected via Triax cable to a LDK5 Base station (CCU) which was standard on the majority of the English OB fleet at the time. To enable to power the LDK 14, a back plate to take a battery could be screwed to the back of the camera, although care must be taken to include spacers, but that is another story. I am not sure if the battery mounting plate was available from the start as I seem to remember going around Liverpool with a car battery to power our spare LDK 14 when asked to supplement a BBC North booking.

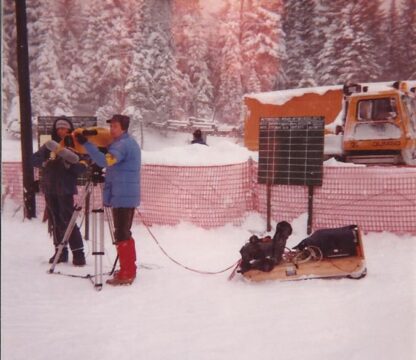

Single camera working 1984

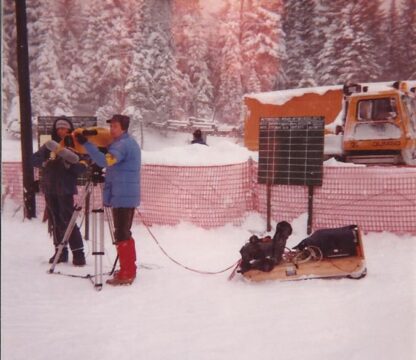

Single camera in the cold 1984

I have mentioned the Cortina estate which I can remember us using on many occasions, this I found out this was the personal BBC car of a senior manager. When the Transport Manager came to observe it being loaded, I was told that it was being overloaded and the interior was in danger of being damaged. This was the last time I was involved with the Cortina, from then a Mercedes estate was hired. As well as having more room the interior was more rugged and there was never any argument of who had the short straw of driving. I could not see the attraction as the only time I drove it, to fill it up with petrol I found it underpowered especially compared to the bigwig’s 2 litre Cortina.

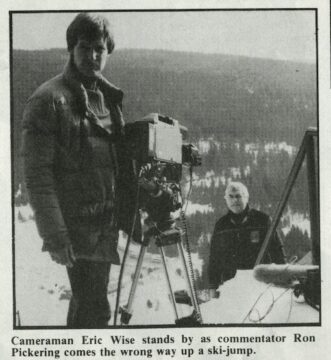

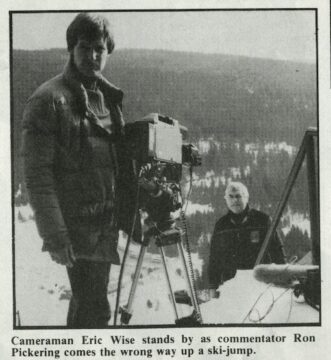

Cameraman Eric Wise at the Sarajevo Olympics, with commentator Ron Pickering on the right

My most memorable trip with our single Camera Unit must be the booking by Sport to go to the 1984 winter Olympics in Sarajevo. We were sent out before most of the London BBC staff to shoot material for a preview program, this would have previously been done on film. During game time we were there to cover interviews and most importantly to do a live interview with Torville and Dean after their final performance. We were not supposed to do live coverage, but we did and London took our coverage rather the official Host Broadcaster coverage. Again another story.

I realised that to use a sack truck in the snow would not be viable and after talking to a TM who was a skier, I concluded that any sack truck needed to have runners. There was not much time to build such a contraption as it had to be sent to London to be shipped out by road with the rest of the equipment required by SCPD (John Harris and his merry men) to build a BBC control room at the IBC. Scenic did the woodwork and Mechanical Workshop did the metalwork: a wooden platform with runners and two detachable wheels.

In the beginning there was no specific kit for these shoots. Various bits and pieces were borrowed from all over the place, or made, or bought on the programme budget, and occasionally hired in, as there was no budget to buy any serous kit. Eventually money was found to build and equip a unit which was named CM3. This was built in-house and I believe that permission had to be obtained to buy a Renault van, as it was BBC policy at the time to buy British, and a van without a transmission tunnel was required.

I was only one of the engineers that worked with a single camera in the early days, probably Ian Dewar did the most including overseeing the creation of CM3.

People used to modern kit probably cannot appreciate the limitations that the available kit at the time imposed on us forty years ago, when the risk of breakdown was very real, and increased once the studio was left behind and increased again once you moved away from multi camera OBs with Camera Vans, later renamed Technical Support Vehicles that carried spares.

Bill Youel, retired BBC Engineer