This year marks the 50th anniversary of the BBC anthology drama series – Play for Today, making it an appropriate time to reflect on our favourites.

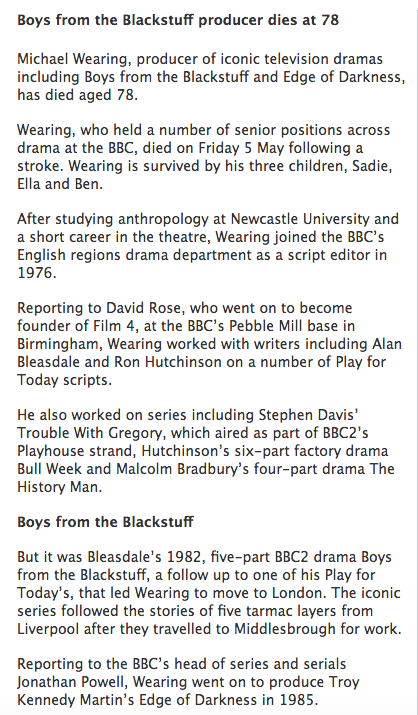

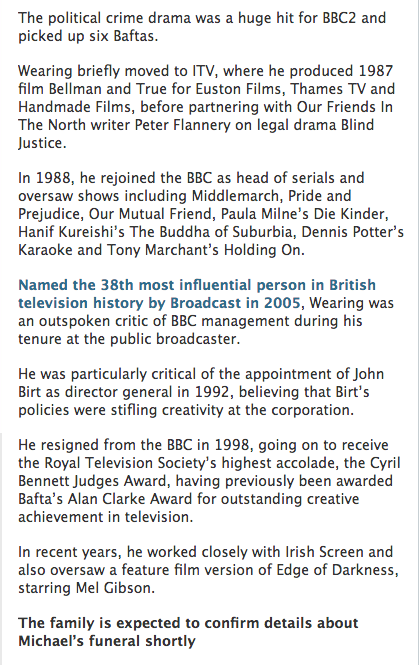

My top five Plays for Today were all filmed by the English Regions Drama department (ERD), at BBC Pebble Mill in Birmingham in the 1970s, when it was led by the renowned producer, David Rose. I worked in the Drama department at Pebble Mill myself in the late 1980s, when Michael Wearing was in charge, and remember the place, the people and the output fondly. Some years ago, I interviewed several of the key programme makers of the Plays for Today listed below and draw on their memories for this blog.

All the Plays for Today discussed here have something unusual or innovative about how they were made, which is why I have chosen them. They illustrate the quality and range of Plays for Today made at Pebble Mill. I’ve listed them in chronological order of transmission.

Shakespeare or Bust, written by Peter Terson, produced by David Rose, directed by Brian Parker. Broadcast BBC1 on Monday 8th Jan 1973 at 21.25.

In June 1972 The Fishing Party, by Peter Terson, was broadcast. It was the story of three miners on a weekend fishing trip to Whitby. Producer, David Rose thought the characters, Art, played by Brian Glover, Ern, played by Ray Mort and Abe, played by Douglas Livingstone demanded another story or two, which he made sure they got. He suggested taking them on a canal narrow boat trip from Birmingham to Stratford Upon Avon. Writer Peter Terson went on the canal trip himself, and David expected that by the end of it he would have an idea for the play. Instead, he had a completed script, with Peter writing on the boat as he went.

Tara Prem was the script editor and remembers being phoned from lock-keepers’ cottages along the route and told there were another 30 pages for her to come and collect. After several trips to collect the bundles of pages, the script was complete.

The miners were on a pilgrimage to see Anthony and Cleopatra at the Royal Shakespeare Company, sadly they don’t get into the theatre, there being no seats left, and instead they meet the actors playing Anthony and Cleopatra, Richard Johnson and Janet Suzeman, outside the RSC and get the Shakespeare from them. Peter had not exactly decided on the ending, saying to Tara that the miners meet the actors, and that she should sort out what happened after that. The sorting it out, seemed to involve everyone swimming in the river in the dark.

Penders Fen, written by David Rudkin, produced by David Rose, directed by Alan Clarke. Broadcast on Thursday 21st March 1974 at 21.25

Pender’s Fen was the third play written by David Rudkin produced at Pebble Mill, the others being shorter dramas, Bypass (BBC2 1972) and Atrocity (BBC2 1973). It is an astonishing film, and very different from the harsh realism usually associated with Rudkin. We have a sixth former, Stephen, in love with Elgar’s music, who has awakened pagan forces within the local landscape. It has surreal elements including a macabre and memorable hand-chopping off scene.

David Rudkin explained that the drama explores several simultaneous contradictory dimensions of reality, including shared and unshared realities. It was visionary writing. There was great difficulty in transferring it to the screen without it looking clumsy, which was partly to do with how discreetly those elements were shot (this would be much easier to achieve nowadays using CGI). David thought the Elgar scene was tremendous, because of its physicality and truth, but felt that the scene with Penda on the hillside at the end lacked mystery. The piece was outside the comfort zone of director Alan Clarke, who was known for directing gritty dramas. According to David Rudkin, Alan felt insecure about the musical and theological dimensions, but trusted his advice to leave all those elements to him, and just deal with the emotion, which Alan did.

David Rose told me of the delight he took in looking at David Rudkin’s scripts, with their beautifully laid out pages, their precision and the puzzles placed on the page. He said he did not know entirely what Pender’s Fen was all about, but that he was happy with that. His mother had never said anything to him about his work in television except for Pender’s Fen, which she said haunted her for three days and nights, which pleased him.

Gangsters, written by Philip Martin, produced by Barry Hanson, directed by Philip Saville. Broadcast on BBC1 on Thursday 9th January 1975 at 21.25.

The Radio Times billing for Gangsters reads:

Blackmail, extortion, drug-peddling and the ‘Blackbird Run’ of illegal immigrants to the West Midlands… How involved is Rafiq, the respected Indian community leader? Rawlinson, the night-club owner? In this hard adventure story, released prisoner John Kline comes up against his old enemies – the gangsters.

Gangsters was a ground-breaking film, inspired after David Rose saw French Connection in the cinema. David gave Philip Martin a writer’s stipend to spend three months in Birmingham to see if he could come up with an idea for a film. Martin researched police corruption, the criminal underworld, and the nightclub scene. The landscape of Birmingham figured strongly, even including an actual speed car chase along the Aston Expressway, which resulted in the crew being pulled over and reprimanded by the police.

There was a lot of sensitivity at the time about how race and people from different backgrounds were depicted, because in Gangsters there were just good and bad people and they might be black, white or Asian. This led to nervousness within the BBC about the film. The great and the good of the BBC, including the controllers and some heads of department, gathered in London to watch the film a few days before transmission. They reacted very favourably to it and only asked for just one edit. There was a shot of a black woman with electrodes on her nipples and they wanted this cut. The director, Philip Saville, said he could edit the visual, but not the sound, so a reaction shot of another character looking was inserted, which David Rose thought made the scene more frightening.

Gangsters got a very good audience and was developed into two prime time series for BBC1.

Nuts in May written by Mike Leigh, produced by David Rose, directed by Mike Leigh. Broadcast on BBC 1 on Tuesday 13th January 1976 at 21.25.

This is almost certainly the best known of Pebble Mill’s Plays for Today, but Mike Leigh’s first television drama for ERD was a half-hour studio piece called Permissive Society in 1975, which led indirectly to Nuts in May. At first, a lot of BBC staff were rather nervous of Mike Leigh’s improvisatory way of working. The crew would be chatting in the canteen saying, there’s a guy down there in the studio and they’re making it up as they go along, which fails to appreciate Mike Leigh’s careful observation of the actors interacting as the characters and developing storylines from those interactions.

David Rose originated from Dorset and was keen to depict the area, as part of the ERD remit to reflect life outside of London. There seemed to be few writers from the South West, and therefore he invited Mike Leigh to make a film set around the Isle of Purbeck: Nuts in May was the result.

David was delighted that the characters of Candice-Marie and Keith were so vivid that they lived on in the memories of the audience for many years, chewing their food very ,very slowly and carefully, and driving round the lanes in their Morris Minor, whilst encountering wild Brummies in local camp sites.

Licking Hitler, written and directed by David Hare, produced by David Rose. Broadcast on BBC1 on Tuesday 10th January 1978 at 21.25.

A glowing review in The Times summed the play up thus, “Licking Hitler began with unnerving brilliance – impeccably in period and hypersensitive to feeling and mood.”

David Hare won the BAFTA for best single television play for Licking Hitler in 1978. Remarkably, it was his television directorial debut. Set in an English stately home in 1941, it tells the story of Anna, played by Kate Nelligan, who is thrust into a secret world, broadcasting propaganda to Nazi Germany. After the war, Anna, and Archie, the chief writer of the now disbanded unit, played by Bill Paterson, long for the meaning of their wartime work, and the excitement of their former lives. It was shot at Compton Verney House in Warwickshire.

Peter Ansorge, who script edited the play and was a friend of David Hare, thought it astonishing that Hare was allowed to direct it, having never directed television before. Even in the late 1970s it was a tremendous risk to give a high profile and complex drama to someone without television experience. However, it paid off, and Peter acknowledges that no one could have made the film better. It was Peter who brought David Hare to television and helped him overcome the prejudices he had about it as a medium.

David Rose described Licking Hitler as an absolute gem, that he could just keep on watching. He had seen a number of plays of David Hare’s in the theatre and had no qualms about him directing, saying he appreciated how precise he could be and how he knew exactly what he wanted to do with the script.

Interviews with the following programme makers have been used in this blog:

David Rose (d.2017) – producer and Head of ERD

Tara Prem – script editor and producer at ERD

David Rudkin – writer Pender’s Fen

Barry Hanson (d.2016) – script editor, producer and later Head of Drama at Pebble Mill

Philip Saville (d. 2016) – director of Gangsters

Michael Wearing (d. 2017) – script editor, producer and later Head of Drama at Pebble Mill

Peter Ansorge – script editor and producer at ERD