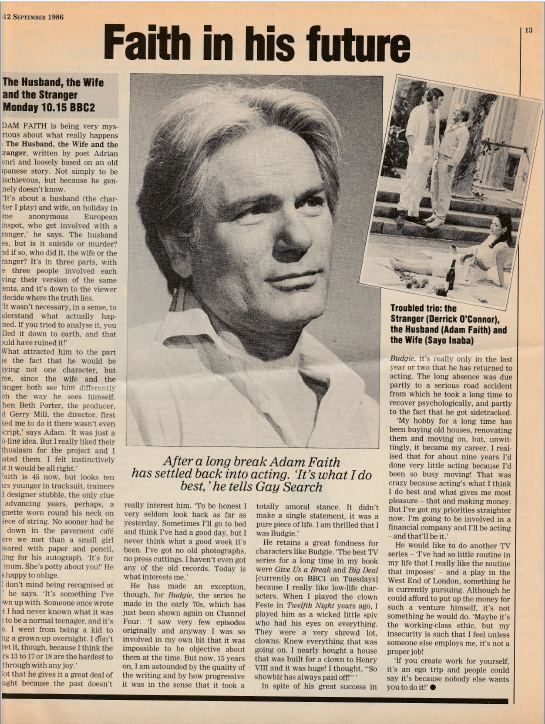

Sayo Inaba and Adam Faith, in The Husband, the Wife and the Stranger. Copyright resides with the original holder, no reproduction without permission

This is an excerpt from Beth Porter’s autobiography, Walking on My Hands, Chapter 12, My Life in Comedy: Comedy in My Life, about her production of the drama:

The Husband, the Wife and the Stranger, BBC2 1986

“Waiting for me back in Birmingham was the chance to produce my first piece of drama. It was a studio piece based on an idea to adapt two Japanese stories by the actress who was to play the lead. I had no idea whether the head of department, Robin Midgley, had already explored the development of the piece, but I wasn’t shown any pre-existing material.

I did, of course, know that the stories had been filmed by one of my cinematic heroes, Akira Kurosawa as Rashomon. The premise is that a tale of love and betrayal is told from three separate points of view. The first challenge was to find a suitable writer. I fixed on the idea of asking Adrian Henri, one of the famer Liverpool poets whom I’d known for decades. It seemed to me that his sensibilities would be just the approach needed to confront the moral ambiguities of the premise as well as presenting the implied sex and violence without any prurient overtones.

I was delighted when Adrian agreed, and while he was writing I got on with finding a director. Robin suggested teaming up with Roger Graef, the brilliant American documentary maker who was keen to get into drama. But as much as I admired him, I wanted a safety net of a director whom I knew could juggle schedules, actors, and unforeseen trouble, should there be any. I really thought this would be a great opportunity to create a bonded company feel, and when Robin agreed to my suggestion that Andy Roberts take oversight of the music, I felt we were on the way.

I asked Gerry Mill who directed me so brilliantly in Howard Schuman’s Anxious Anne. He had a great reputation with actors and was familiar with the demands of drama. Because the whole project had been the idea of the Japanese actress, we were committed to her. So Gerry and I drew up independent lists of the two actors who’d complement each other on screen. On both our lists was Derrick O’Connor whom I’d appeared with all those years ago in the James O’Herlihy plays at The Bush Theatre. He was available and keen to be involved.

We wanted to try to get a name that audiences would recognise to raise the profile of a studio piece, and we hit on a great idea. At the time the ever-popular singer, Adam Faith, was appearing in the West End, having publicly declared he wanted to do more acting. He’d had a big success some years previously with his TV series Budgie. Both Gerry and I liked his open fresh-faced appeal which had the potential to turn a bit nasty. Whereas Derrick could do nasty in his sleep, but we knew he could also play the victim.

We went to see Adam’s play and took him out for a meal. Happily, he agreed to do Adrian’s play. Now, all we needed was the play! For whatever reason Adrian was stalling. Uh-oh!

Gerry and I set out for Liverpool as on a military mission. Come back with the script, lads, and don’t get caught by the enemy! Actually, it was a scene from a sit-com. I sat with Adrian talking through the next scene, and he set to work typing. As soon as he had a few pages, I’d take them to the next room for Gerry to read. On we went like that, through the night, till the script was ready.

Actually, it was bloody good! Adrian did know exactly what to do. I guest his reluctance was down to nerves and insecurity. Yes, folk, artists – even great ones – get insecure. It’s only despots who think they know everything. The trick is to acknowledge the vulnerability and work through it, trusting your instincts and experience.

Gerry was terrific with the cast, allowing them the space they needed to inhabit the characters. The crew were keen to enter into the spirit of this unusual studio piece. I was keen to incorporate some of the more recent digital effects that were being developed for cinema, and Gerry trusted me to liaise with the editor to ensure our vision was melded with Adrian’s. We also had the bonus of Andy Roberts in control of the music.

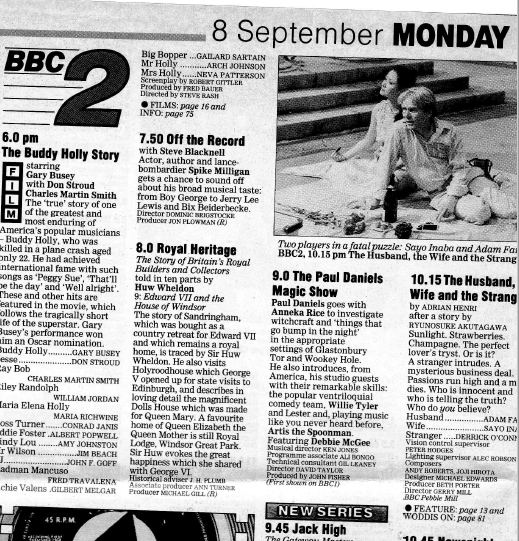

We got lots of publicity, mostly due to Adam’s presence. The Radio Times devoted a full page to him. The half-hour play went out at 10.15pm on BBC2 on Monday, 8 September 1986. We got lots of feedback. And I was probably having a mini-breakdown trying to adust to life as a reluctant singleton. An ageing reluctant singleton. An overweight ageing reluctant singleton.”

Thanks to the producer of the drama, Beth Porter, for sharing this excerpt.

Beth Porter’s (long and amusing) autobiography Walking on my Hands, is available for a couple of pounds on Kindle, on the link below. Chapter 12 includes Beth’s adventures with the BBC.

Below is the Radio Times entry for the drama, from the BBC Genome project:

http://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/a0ac4ec29e33434fb1ad17ff13426474

“The Husband, the Wife and the Stranger

by ADRIAN HENRI after a story by RYUNOSUKE AKUTAGAWA

Sunlight. Strawberries. Champagne. The perfect lover’s tryst. Or is it?

A stranger intrudes. A mysterious business deal.

Passions run high and a man dies. Who is innocent and who is telling the truth? Who do you believe?

Vision control supervisor PETER HODGES

Lighting supervisor ALEC ROBSON

Composers ANDY ROBERTS, JOJI HIROTA Designer MICHAEL EDWARDS Producer BETH PORTER Director GERRY MILL BBC Pebble Mill

Contributors

Author: Adrian Henri

Director: Gerry Mill

Producer: Beth Porter

From Stories By: Ryunosuke Akutagawa: The Roshomon Gate

Vision Control Supervisor: Peter Hodges

Lighting Supervisor: Alec Robson

Musical Supervisor/Composer: Andy Roberts

Designer: Michael Edwards

Husband: Adam Faith

Wife: Sayo Inaba

Stranger: Derrick O’Connor”