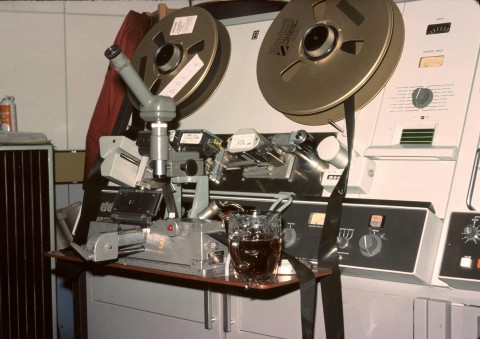

Photo of Jim Hiscox in VTB

Editing with Quad

As mentioned earlier cut editing was not feasible for videotape, so all editing was performed using “Dub” edits, and in sequence. The editor would decide which piece he wanted from the play in tape, and a cue point would be marked 10 seconds prior to that on the back of the tape with a china-graph pencil. The electronic editor on the record / edit machine recorded a cue pulse on the edit tape to initiate the electronic editor. This performed the switching sequence to switch the record machine from playback to record at the edit point, and involved careful timing of record and erase circuits, in order to create a seamless join. The Edit machine could work in Assemble or Insert edit mode. Assemble meant joining a new recording to the end of a previous one, and the new recording would then continue until the stop button was pressed. Insert recording was used to add a new section of pictures ( or sound) to an already existing section of recording which had to be continuous. The control signal that is recorded during a standard recording, or Assemble edit, was not re-recorded in insert mode, and as this was the equivalent of film sprocket holes, had to be continuous for a stable playback. This meant that insert edits could not alter the overall duration of a recording, and that the section being inserted had to be the same duration as the one being removed.

Most programmes were assemble edited, starting with the line-up, and VT Clock (in those days a mechanical clock in the studio). Then the opening title sequence, which would often have come from film. VTA was the play machine, which could be used to do simple “on the fly” edits, whereas VTB had the Editec controller which allowed for some adjustment of edit points. The procedure was, locate the in point on the playback machine and wind back 10 sec, marking the tape (physically), locate the in point on the record machine, marked with a pulse, wind back 10 sec and mark the tape physically. Remote the play machine, switch on the editec and then run both from the record machine. If the in point was at a shot change from the player, it was quite important to check the edit point for flash frames. The nature of the colour TV signal meant that editable points were always 2 frames apart, and for a given sync point on the recorder, it was possible that if the in point on the player was on the non editable frame, the machines might sync on the wrong frame giving a flash frame. This was adjusted by physically moving the tape either forward or back from the china-graph mark when re-cuing.

In respect of Quad editing, John Lannin was a master of the craft. I remember him, and I think Steve Critchlow working for several days of edit sessions putting together a title sequence (Might have been for “Gangsters”) which comprised a long series of flash frames, probably no more than 4 frames of any clip. The effect was truly stunning. There must have been 300 or more edits, and each one needed a 10 second run up, both to locate the shot and to edit it into the sequence, and finally to review it. No wonder it took a long time.

With every edit the recording went to another generation, due to the fact editing was a playback and re-record process. Also because the sequences all had to be laid down on the tape in order, it meant that to re-arrange the order meant another edit, and hence another generation. Ideally the best that could be achieved was 2nd generation, where the final edit was the first edit. For a lot of programmes a first edit was fine tuned by a second edit, leading to 3rd generation. However for programmes like ‘Pebble Mill at One’, inserts would often come from previously edited programmes or shows, so by the time they appeared in a ‘Pebble Mill ‘Highlights programme would be 5th or 6th generation, by which time the recording deficiencies start to become obvious. This has been something of a problem for archives, as often the original early generations have often been wiped, or the original source lost in the trail of hand written records. No wonder everyone welcomed digital recording with the infinite generation promise of fidelity, but that did not come for nearly another 20 years.

Ray Lee