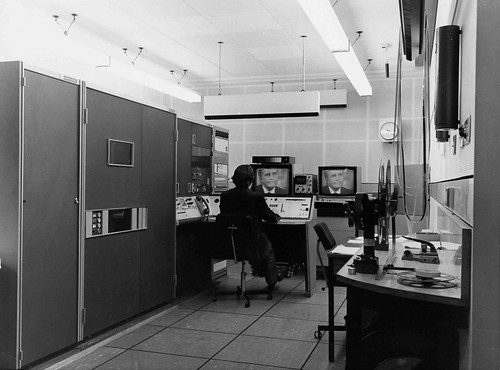

Photo by Ivor Williams, no reproduction without permission. Photo from 1971, of the Rank Cintel 16mm Flying Spot Telecine Machine.

The majority of inserts to Midlands Today, and Pebble Mill at One were on film in those days (mid 1970s), as this was before lightweight cameras, and film cameras were at that time the best means to obtain location shots. Studio inserts were often recorded on VT then played in live quite often without editing. Film was much easier to edit then.

The process of getting a news story involved a film camera crew going out, shooting on film with sound onto tape. The tape also recorded a pilot tone from the camera to allow re-syncing of the sound after editing. The film (usually reversal film) then went into Film processing while the tape was transferred to Sepmag using the pilot signal to lock to the sepmag bay, thereby giving the sound track frame for frame correspondence with the film. The two parts then came back together in the film cutting room, where the film editor selected the parts he wanted using a Pic Sync ( basically a set of about 4 sprocket wheels on a shaft, with an illuminated mini projector on the far end to see the film images. The sepmag track (or tracks) would be on the nearer sprockets. On either side was a film bin. Often a “wild” track sound was recorded (not sync to pictures) in order to add additional effects and bridge edit points. The Clapper board was used to sync the sound and picture together with giving details of what item this was. The film editor would look for the first frame on which the clapper was completely closed, and align that with the clap on the soundtrack, thereafter the sprockets would ensure that the sound and picture remained in sync.

With news stories there was not usually time to go into dubbing, so the edited film and sound track then came straight to TK and one hoped that the edits on the sepmag would hold together.

Where time permitted a dub the sound was often tracklaid. This allowed sound to be carried over an edit to smooth the effect. In this case the sound was edited into 2 or more rolls with film spacer being used to make all the rolls the same length. Each roll would have a leader spliced onto it with the familiar sync cross and then a 12 second count down.

At the dub, the film projector and the sound rolls on the sepmag bays would all be locked together electrically so the they ran synchronously. The machines would be laced and set with the cross in the projector gate and on the sepmag sound head, and then the lock button pressed which linked everything together. Due to the nature of the electrical locking, very occasionally the sepmag bay would go into runaway, and one needed to hit the stop button fast, otherwise there was a danger that the film sprockets would be damaged, and a lot of film could end up very quickly on the floor!

Dubbing involved balancing and mixing the soundtracks together, adding any voice overs, commentary, and spot effects, and recording the whole sequence onto a new continuous sepmag track. At the end of the process there would be a single continuous sepmag track and a single edited picture track, which could then be played by TK into the studio.

The process was the same for network programmes on film, although in this case the film was usually shot on negative film, and a rushes print made. This is what the editor used to compile the required shots and soundtracks. The edited rushes were then returned to the lab for a print to be made from the original negative, using the rushes edit to align the required shots. The lab also graded the pictures at this stage to match the exposure and colour balance to some extent. This print was termed the “answer print”. This was usually the one used be dubbing, and sometimes also for transmission, although some programmes had a Transmission print made as well. The answer print basically gave an opportunity to the producer to change his mind, and for the lab to further trim the grading of pictures, although as it entailed quite a lot of expensive processes, in later years the answer print was quite often the transmission print as well.

By the time it got to TK there was usually a picture roll, and a sepmag sound roll. In a few cases (usually prints of commercial films) the sound was an optical track on the picture roll, in which case there was no separate sound. However this gave rise to problems if ever the film needed to be cut and spliced as the sound head was separated by 16 frames from the film gate so the picture would change, and the sound continue, only to change about half a second later.

In the case of news it was not uncommon for the editor to rush in with the film and sepmag rolls with very little time to get it on the machine before transmission. The one occasion I particularly remember involved me, and I think Jim Gregory, lacing the sepmag and picture rolls simultaneously, hitting the lock button and running the machine without even pausing on the “10” while Tom Coyne padded until the film hit the screen. Usually there was a little more time, and quite often we had a quick rehearsal, prior to the programme going out.

R. G. Lee